Reader Josh C wrote in with one solution to a problem that’s been frustrating me for months. When you want to save a script as a .pdf, Final Draft won’t always include the title page. It’s frustratingly inconsistent. The obvious workaround is to save the title page as a separate file, which is what I’ve often done. But then you end up emailing two documents, increasing the confusion on the other end.

Josh was using Final Draft version 6.0.6.0. It turns out, the issue is whether the “Title Page…” window is open or closed.

1. Save your screenplay as normal (as a .fdr)

2. With your saved screenplay still open, go to Document > Title Page. A new, blank Title Page opens.

3. Fill in the blanks, then just CLOSE THE TITLE PAGE. This is the part that I got hung up on forever. If you leave the title page open, then try to save as a PDF, it won’t work. The Title page WON’T attach itself to the PDF if the Title Page is still open when you try to Save as. Just close the Title Page. It saves automatically to your screenplay.

4. With your screenplay still open, go to File > Save As — then select Adobe Acrobat Document (*pdf) - or whatever your computer says. Save the new PDF file somewhere and open it up. The Title Page should be attached at the top of the screenplay where it should be

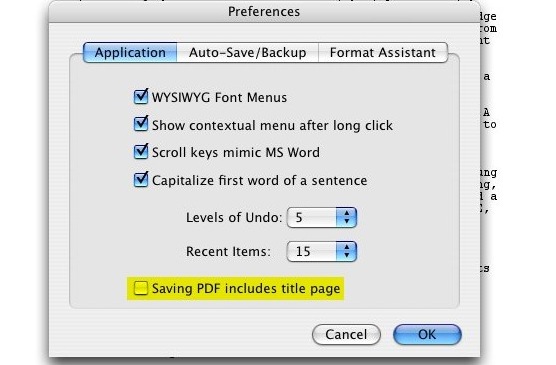

In my tests with 7.1.3, the .pdf will also include the title page even if that window is still open1 — provided you have a certain checkbox checked in “Preferences.”

Yes, I’ll admit that I didn’t read the manual with version 7 of Final Draft. But this is a pretty questionable place to put this checkbox. After all, sometimes you’ll want to include the title page, sometimes you won’t. Does it really make sense to have this be an application-wide preference, housed in a panel that has nothing to do with printing, saving or the specific document you’re working on? It’s pretty much the last place I’d think to look for it.

Yes, I’ll admit that I didn’t read the manual with version 7 of Final Draft. But this is a pretty questionable place to put this checkbox. After all, sometimes you’ll want to include the title page, sometimes you won’t. Does it really make sense to have this be an application-wide preference, housed in a panel that has nothing to do with printing, saving or the specific document you’re working on? It’s pretty much the last place I’d think to look for it.

What’s more, at least on the Mac, Final Draft is using the built-in .pdf facility of OS X. It’s basically just printing to a file.2 Since it seems to be using the standard print architecture, you’d think that choosing the “Print Title Page” option in the Print dialog box would have some effect. It doesn’t. And that’s why it’s frustrating.3

Whenever I complain about Final Draft, I get a nice note from the developers asking me to help out with the next version, and a few emails from companies working on competing applications. So let me make it clear where I stand. Despite its annoyances, I end up using Final Draft because what it gets right generally outweighs what it gets wrong. There’s certainly some inertia on my part, but given a better alternative, I’d switch in a heartbeat. The shipping versions of Screenwriter, Montage and Celtx aren’t better, particularly when it comes to revisions.

I’m hoping the upcoming Screenwriter 6 gives Final Draft some real competition, because that’s what’s lacking. When we were cutting The Nines, I realized that editing software has benefitted tremendously from the battle between Avid and Apple, with new features, better interfaces, and dramatically lower prices. I started out a Final Cut Pro man, while my editor was firmly Avid. We had the luxury of both being right. Both systems are terrific, and I think that’s largely because of the competition.

- However, if you haven’t closed or saved the title page, it won’t be updated until you do. ↩

- You can test this by choosing a two-page layout in the Print dialog box. The next time you choose to Save as PDF, you’ll get facing pages. ↩

- On the Mac, you always have the option of using the “Save as PDF” function built into the Print dialog box. But I’ve never had any luck getting that to include a title page. My guess is that Final Draft treats the title page as a separate document. When you print to a traditional printer, you’ll notice a one-page progress dialog flash for a second. I think Final Draft is kicking out the title page as a distinct job. It never incorporates it into the “real” script. ↩